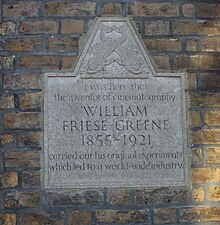

Cinematic inventor

Experiments with magic lanterns

In Bath he came into contact with John Arthur Roebuck Rudge. Rudge was a scientific instrument maker who also worked with electricity and magic lanterns to create popular entertainments. Rudge built what he called the Biophantic Lantern, which could display seven photographic slides in rapid succession, producing the illusion of movement. It showed a sequence in which Rudge (with the invisible help of Friese-Greene) apparently took off his head. Friese-Greene was fascinated by the machine and worked with Rudge on a variety of devices over the 1880s, various of which Rudge called the Biophantascope. Moving his base to London in 1885, Friese-Greene realised that glass plates would never be a practical medium for continuously capturing life as it happens. Hence he began experiments with the new Eastman paper roll film, made transparent with castor oil, before turning his attention to experimenting with celluloid as a medium for motion picture cameras.

Movie cameras

In 1888, Friese-Greene had some form of moving picture camera constructed, the nature of which is not known. On 21 June 1889, Friese-Greene was issued patent no. 10131 for a motion-picture camera, in collaboration with a civil engineer, Mortimer Evans. It was apparently capable of taking up to ten photographs per second using paper and celluloid film. An illustrated report on the camera appeared in the British Photographic News on 28 February 1890. On 18 March, Friese-Greene sent details of it to Thomas Edison, whose laboratory had begun developing a motion picture system, with a peephole viewer, later christened the Kinetoscope. The report was reprinted in Scientific American on 19 April. In 1890 he developed a camera with Frederick Varley to shoot stereoscopic moving images. This ran at a slower frame rate, and although the 3D arrangement worked, there are no records of projection. Friese-Greene worked on a series of moving picture cameras into 1891, but although many individuals recount seeing his projected images privately, he never gave a successful public projection of moving pictures. Friese-Greene's experiments with motion pictures were to the detriment of his other business interests and in 1891 he was declared bankrupt. To cover his debts he had sold the rights to the 1889 moving picture camera patent for £500 to investors in the City of London. The renewal fee was never paid and the patent lapsed.

Colour film

Friese-Greene's later exploits were in the field of colour in motion pictures. From 1904 he lived in Brighton where there were a number of experimenters developing still and moving pictures in colour. Initially working with William Norman Lascelles Davidson, Friese-Greene patented a two-colour moving picture system using prisms in 1905. He and Davidson gave public demonstrations of this in January and July 1906 and Friese-Greene held screenings at his photographic studio.

He also experimented with a system which produced the illusion of true colour by exposing each alternate frame of ordinary black-and-white film stock through two or three different coloured filters. Each alternate frame of the monochrome print was then stained red or green (and/or blue). Although the projection of prints did provide an impression of colour, it suffered from red and green fringing when the subject was in rapid motion, as did the more popular and famous system, Kinemacolor.

In 1911, Charles Urban filed a lawsuit against Harold Speer, who had purchased rights in Friese-Greene's 1905 patent and created a company 'Biocolour', claiming that this process infringed upon the Kinemacolor patent of George Albert Smith, despite the fact that Friese-Greene had both patented and demonstrated his work before Smith. Urban was granted an injunction against Biocolour in 1912, but the Sussex-based, racing driver Selwyn Edge funded an appeal to the High Court. This overturned the original verdict on the grounds that Kinemacolor made claims for itself which it could not deliver. Urban fought back and pushed it up to the House of Lords, which in 1915 upheld the decision of the High Court. The decision benefited nobody. For Urban it was a case of hubris because now he could no longer exercise control over his own system, so it became worthless. For Friese-Greene, the arrival of the war and personal poverty meant there was nothing more to be done with colour for some years.

His son Claude Friese-Greene continued to develop the system with his father, after whose death in the early 1920s he called it "The Friese-Greene Natural Colour Process" and shot with it the documentary films "The Open Road", which offer a rare portrait of 1920s Britain in colour. These were featured in a BBC series The Lost World of Friese-Greene and then issued in a digitally restored form by the BFI on DVD in 2006.