Professional career

class=notpageimage|

Scottish lighthouses constructed by Robert Stevenson

Stevenson served as an apprentice civil engineer to his stepfather, Thomas Smith. He was so successful at it that, at age 19, he was given responsibility for supervising the erection of a lighthouse on Little Cumbrae island in the River Clyde. His next project was overseeing the building of lighthouses on Orkney. While working on these projects, he continued his civil engineering studies: He diligently practised surveying and architectural drawing, and attended maths and physics lectures at the Andersonian Institute in Glasgow.

In the winter, when it was too chilly for construction work, he attended lectures at the University of Edinburgh in philosophy, mathematics, chemistry, natural history, moral philosophy, logic, and agriculture. He was not granted a degree because he did not have the proficiency in Latin or Greek that was a requirement for a degree in those days.

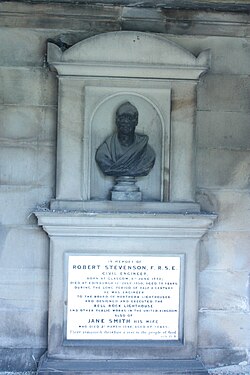

In 1797, he was appointed engineer to the Lighthouse Board, succeeding to his stepfather's place there. In 1799, he married Smith's eldest daughter Jean, who was also his stepsister, and, in 1800, Smith made him his business partner.

The most important work of Stevenson's life was the Bell Rock Lighthouse, built between 1807 and 1810 when he was in his mid-30s. The lighthouse still stands today. Its construction was a scheme long in the gestation, and then long (and extremely hazardous) in the construction. Its structure was based upon the design of the Eddystone Lighthouse, which had been built by John Smeaton — but Stevenson made several improvements to that design. John Rennie was a consulting engineer on the project. After the project was complete, there was some contention as to who should get more credit—Rennie or Stevenson. That contention grew particularly strong as between the two men's sons when they were older - Robert's son Alan Stevenson and John Rennie's son, Sir John Rennie.. Samuel Smiles, a popular engineering author of the time, published an account taken from Rennie, which gave prominence to Rennie's claim. However, the Northern Lighthouse Board gave full credit to Stevenson, as have historians since then.

Stevenson's work on the Bell Rock and elsewhere provided a fund of anecdotes about the dangers he tended to place himself in and his lucky narrow escapes. For example, in 1794, he was aboard the sloop Elizabeth of Stromness, returning from the Orkney Islands, when it became becalmed off Kinnaird Head. Unlike others aboard the ship, he had the good fortune to be taken off it and rowed ashore. After he left it, a gale arose and drove the ship back to Orkney, where it foundered: All aboard were drowned. Another time, he was with a crew of men on the Bell Rock, which was only above the surface of the water at the lowest tide, when one of the crew boats drifted away. The remaining boats did not have enough room to carry everyone back to the mainland. Once the tide rose, the rock would have been submerged, and anyone not in a boat would have been stranded in the water. Luckily, before the tide rose, the Bell Rock pilot boat happened to arrive on an errand to deliver some mail to Stevenson, and thus saved the situation.

Stevenson served as the engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board until 1842 - nearly fifty years. During that time he designed numerous lighthouses and oversaw their construction and the addition of later improvements to them. His many innovations included his choice of light sources and mountings, his reflector design, his use of Fresnel lenses, and his use of rotation and shuttering systems that provided lighthouses with individual signatures (characteristics) — allowing them to be identified by seafarers. For this latter innovation, he was awarded a gold medal by King William I of the Netherlands.

Engineering skills were in high demand after the Battle of Waterloo, which marked the end of the continental wars, as the focus turned toward improving the country's infrastructure. So Stevenson was kept busy. In addition to his work for the Northern Lighthouse Board, he served as a consulting engineer on many projects, collaborating with other engineers such as John Rennie, Alexander Nimmo, Thomas Telford, William Walker, Archibald Elliot, and William Cubitt. These projects included the construction of roads, bridges, harbours, canals, railways, and aids to river navigation. He designed and oversaw the construction in Glasgow of the Hutcheson Bridge, and in Edinburgh of the Regent Bridge and approaches to it from the east. He also produced a number of designs for canals and railways which were not built, and new and improved designs for bridges, some of which were later implemented by his successors. He invented the movable jib and the balance crane as necessary aids to lighthouse construction, and, as George Stephenson noted, he led the trend toward using malleable rather than cast-iron rails in the construction of railways.

In 1815, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. His proposers were John Barclay, John Playfair and David Brewster.

In 1824, he published a paper about the condition of the eastern coastline of the United Kingdom, entitled Account of the Bell Rock Lighthouse. In it, he presented convincing evidence that the North Sea was eroding that coastline, and in particular that the great sandbanks were disappearing — the spoils taken by the sea. He hypothesized that freshwater and saltwater areas at river mouths exist as separate and distinct streams, and carried out tests of this hypothesis. He contributed articles to the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Edinburgh Encyclopædia, and published papers in a number of scientific journals.

He was inducted into the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame in 2016.